A writer who critiques her own work has a fool for a critic.

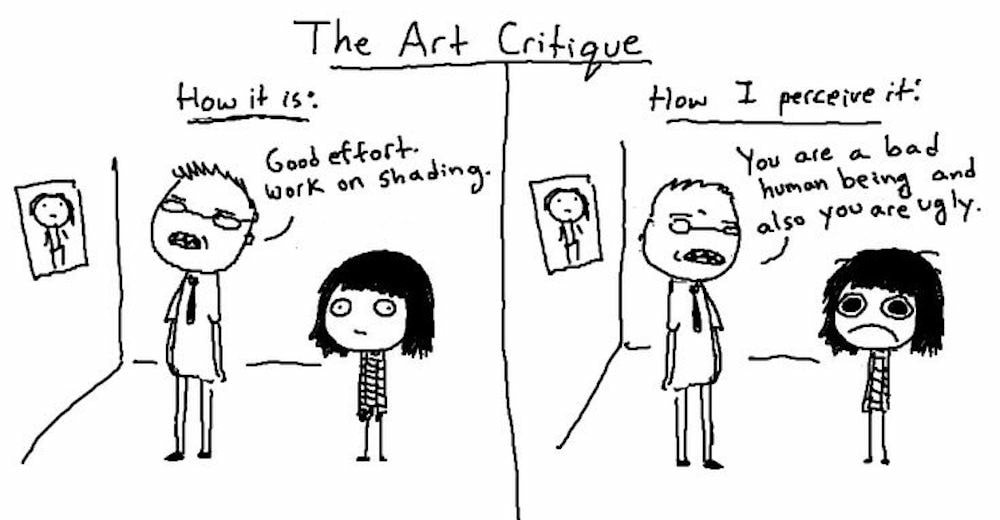

We fear honest critique, but it is possible to learn how to critique writing in a helpful way.

But a critical fool wielding careless words at a writer can cause more damage than they might realize.

Whichever side of the creative process you find yourself, consider making the effort to learn the fine art of how to critique writing in a manner that is helpful. Giving and receiving a helpful critique can be a huge challenge, especially if you’re new at it.

In this article, I’ll discuss the do’s and don’ts of exchanging a helpful, actionable critique, and offer a technique that works especially well for empathic, socially-aware, and feminist writers.

Just like other forms of communication, healthy, helpful critique is all about boundaries, and establishing clear guidelines can make a huge difference in how (or if) a feedback loop functions.

Sloppy critique causes conflict. Careful critique causes improvement in both the critic and the artist, and leads to collective synergy plus top-quality creative results.

How to Critique Writing: DO’s and DON’Ts of Creative Critique

These don’t just apply to written work. As you read through the list, imagine applying these ideas to critical dialogue of all kinds.

We’ll start with the DON’Ts.

- DON’T lie about having read the piece. If you couldn’t get through it, be honest and tell the writer why. If you never got around to it, be honest about that too. But whatever you do, don’t rush through the reading and give a hurried, lazy critique. It won’t help anybody, and it could do some real damage to a fledgling writer’s motivation.

- DON’T tell other people about what you read or show the work to anybody without express permission from the author. This is a private, confidential transaction.

- DON’T focus on preference. Critique isn’t about whether or not you like, agree with, or approve of the. Focus more on structure, syntax, language, and dynamic. See if the piece sticks to its subject, and if it comes across as readable, clear, and authentic.

- DON’T choose a work that you already know you fundamentally disagree with or feel triggered by, at least not if you’re new at giving formal critique. It’s better to learn this process with work (and people) that we love. Learning to be triggered by a work and still engage in a productive critique is definitely something you can do, but pace yourself.

And now, the DO’s:

- DO ask the writer what their boundaries are. Yep, there’s that word again: boundaries. So, what are they? What kind of critique do they want? Do they want overall encouragement as a writer, kind words and encouragement only? Or are they looking for a more formal critique of the flow, syntax, readability, and emotional impact of the writing itself, with both positive and negative response?

- If they choose the former, give it to them. Sit down, read the story, zoom in on the three best things about it, and tell your friend what you found. Easy! And, respect that boundary: if you didn’t like it, mum’s the word. If your friend chooses the latter, and asks for a more detailed and balanced response, give it to them (and consider using the EMMA method outlined in the second half of this article).

- DO make time for the critique, and read the work twice. Set aside an intentional moment to read and respond to the work. Read it through once, making no notes at all. Then again, making notes. Then go back through and edit your notes into coherent sentences. If this feels like too much effort then I recommend you simply tell your writerly friend you don’t have time to critique their work. Remember that a clear, intentional critique can work wonders to help a writer improve her work and shed feelings of inadequacy. But a thoughtless, rushed response can also do the opposite.

- DO look for deeper ways to describe your emotions than “I love it,” or “it’s bad.” If you don’t like it and you think it’s bad, articulate a list of actionable, specific suggestions for how the work could be improved, and why you think it should be.

- DO try to think of related works, and note them in as much detail as you can muster. What does this work remind you of? How and why? This information, while it might seem like passing thoughts when you are reading the piece, will be of great import to the writer as she finds her niche, differentiates herself from similar writers, and engages in a lineage that makes sense for her work.

- DO learn to love rejection. Whichever side of the critique you are on, this applies. Be absolutely at ease with the writer rejecting everything you say about her work, and don’t be attached to any of your own ideas about it. LIkewise if you’re the writer being critiqued: take what you can use, reject the rest, and if your reader/critic just isn’t feelin’ it, (or if they didn’t even read it) fuhgetaboutit! No big deal! That’s life and nobody owes you anything. Get on with your life, find another reader, and keep writing.

- DO tune into patterns. If you feel like you’re getting an overwhelming amount of negative feedback or, worse, an underwhelming lack of emotional response at all to your work, you have two choices: stop writing, or write better. If you’re gonna give up, do it now. The last thing the world needs is more semi-committed writers who mope around thinking their work is all crap.

.

.

. - Still here? Great! Know this: the only way to write better is to write more. So, get to it. And the best way to get comfortable with rejection is to experience it often. Get your work out there, be receptive to feedback, tune into what you can take from it, and release what you don’t need.

- DO use an actual technique and process for critique. There are many options, easily googled, offering a wide range of results. I’ll share the one I use in the next section.

Careful process leads to quality product.

A quality critique is equal parts listening, empathy, radical honesty, and contextual assessment. It does not focus on your preference for or aversion to a thing. Instead it asks you to engage in a conversation and create specific, measurable, and actionable suggestions.

Bad critique is usually only the latter: we/they offer a emotion, a reaction, and a string of words based on whether or not we enjoyed or agreed with the work the presentation, based on what’s going on for us in that moment, in our bodies, in our lives. It’s completely subjective, and usually not a critique at all. What passes for critique in most places is actually just opinion, and it’s not the same.

Now, this isn’t to say you shouldn’t critique a piece from your particular zone of bias and expertise. In fact, you should, But be clear with the writer what that bias and expertise is, and articulate actionable ways the piece can more deeply engage in the conversation you think it should be a part of.

Ready? Here we go!

I created this critique method in grad school, when I was working on my MFA about the Heroine’s Journey, and we used it a bunch. It’s fun and it works really well to bring out the best in both writer and critic alike. It’s a combination of two classic techniques, “Empathic” and “Minor-White,” and the other letters stand for Mindful and Actionable. Empathic Minor-White Mindful Actionable=EMMA.

How to critique writing, the 12 steps of the EMMA method:

- Sit with your feet on the floor and your hands on your knees. Close your eyes, and take three full, deep breaths. Swallow and relax your tongue away from the roof of your mouth.

- Take about twenty breaths while you imagine you are a small child, playing happily in a field of colorful flowers. Imagine feeling safe, warm, happy, and at peace with the world.

- As you open your eyes, prepare your mind to take in the work without any judgment, preference, or fear.

- Give the artist or writer your full physical, mental, and emotional attention while you explore the work. If she has given you a document to read, then go to a quiet place, away from distractions, and concentrate. Be present. Engage.

- Release any preconceived notions or expectations from the work or the artist, and ask yourself not: is this good or bad?

but instead:

What is this work about, and what does it say to me?

How does it make me feel?

What does it remind me of?

What direction do I want the conversation to go from here? - Write one paragraph of “I-statements.” Are you sad? Energized? Uncomfortable? Agitated? Confused? Does the work remind you of something about your life and connect to an emotion there? Include in your statement the particular detail that might be provoking your feelings. Get it all off your chest. Get the emotions out of the way.

- Relax, close your eyes, take five long, slow breaths, and return to the field of flowers. Again, be innocent, joyful, happy.

- Write a list of questions about the work. Allow your questions to come from a place of childlike curiosity, rather than from a need to judge the work or the artist.

- Once again, close your eyes and return to the flowers. Five breaths.

- Write a list of suggestions for the writer.

Which other works should she look up?

Which topics need more research?

Do you have suggestions about the way she put her sentences together?

Were there certain words that could have been used differently or replaced?

Does stuff need to be fact-checked? Clarified?

Think in terms of accuracy, readability, and authenticity, and create a to-do list for her. - Make a third list, this time of specific writers, works, and projects that feel connected to what you’ve read. Where is this piece, in the big picture? Where is this writer in the conversation? Think of anything that comes up to help her find her niche.

- At completion, a written EMMA critique looks like this:

I. I-statements

II. List of questions

III. List of suggestions

IV. List of references for lineage and niche - Now you’re ready to send your critique to the writer, but you’re not finished because you’ll need to hold space for her to bounce back at you and respond. She may be defensive, especially if you have criticized one of her darlings, but try to just listen to her reactions without diving back into critic mode. She probably just needs to vent and then she’ll be able to really put your clear, concise comments and thoughtful, task-based suggestions to work!

Alrighty! That’s EMMA, I hope it helps!

Next time somebody asks you for feedback on their writing, keep this stuff in mind, and the next time you’re looking for feedback on your own work, share this with your reader.